Currently In The Richmond Gallery

The Virginia and Howard Richmond Gallery offers regularly changing exhibits ranging from stories of the communities that were once part of Ocean Township to interesting aspects of local history. This Gallery is named in honor of Howard (Doc) and Virginia (Ginny) Richmond, for their years of dedication and service to the Museum and its work.

Beginnings: Ocean Township’s First People

Archaeological digs unearth a surprise

On August 31, 2022, 13 boxes of historical artifacts arrived at the Museum. They contained items, meticulously packaged and catalogued, that were unearthed during a 2019-2020 archaeological study of the former site of the Eden Woolley House on the corner of Rte. 35 and Deal Rd., Ocean Township (referred to as the Eden Woolley Farmstead Site). The artifacts are now part of the Museum’s permanent collection.

The 2019-2020 study was the second on the site. The first took place in 2001-2002 and the artifacts from that investigation are currently in the State Museum.

The reason for the digs

In an effort to identify and safeguard New Jersey’s buried cultural and historical resources, the state requires an archaeological study of certain sites prior to development. These investigations include recommendations for mitigation to protect resources that meet National

Register of Historic Places criteria and may be affected by the construction.

The initial survey of the Eden Woolley Farmstead Site was triggered in 2001 by an application to develop the acres on the corner of Rte. 35 and Deal Rd. That study identified the Eden Woolley House, at that time still on the property, as an historical resource requiring protection. Although the proposed development was never built, the developer honored his commitment to save the building and, in 2005, paid $113,000 to move the house to its current site, 1,100 feet east. The refurbished, relocated Eden Woolley House opened to the public as the Township of Ocean Historical Museum in 2009.

More recently, when the corner property was again scheduled for development, the state required a second archaeological study to update and expand the findings of the first. Our recently acquired artifacts are from this second survey.

The scope of the studies

The 2001-2002 study had focused on the Eden Woolley house, then in its original location, and a section of in the northwest of the property believed to have been a Native American encampment. The state instructed Richard Grubbs & Associate (RGA), the firm hired to conduct the 2019-2020 study, to re-evaluate the original findings, investigate areas of the property not included earlier, and expand the survey of the Native American encampment.

The RGA archaeologists dug 299 one-foot wide test holes (called Shovel Test Pits or STPs) at 50-foot intervals in a grid pattern across the 15.5 acres of the property that had not been previously studied. They created another 65 STPs at 25-foot intervals in the Native American section of the property. Based on the yield of these test holes, additional STPs were dug in the most promising areas. Where findings warranted, Evacuation Units (pictured in the insert to the left) and trenches were dug. Soil was sifted through wire mesh. The items found were carefully cleaned and catalogued.

What they learned

The experts studied property deeds, church records, contemporary accounts, and comparable sites to interpret the newly found artifacts and piece together the story they tell. The 2019-2020 study yielded insight into the time period, settlement pattern, and activities of the Native Americans who occupied the site—and it unveiled a big surprise.

The Native Americans

Together, the 2001-2002 and 2019-2020 studies unearthed 776 prehistoric artifacts, including remnants of tools used for cutting, shards of ceramic containers, and fragments of burned rock..

Based on the quantity, age, nature, and location of the artifacts, the experts hypothesize that Native Americans used the site as a short-term encampment, visited repeatedly over thousands of years beginning as early as 6500 B.C. and continuing through 1600 AD. They travelled in small bands from larger inland communities to take advantage of seasonal natural resources. The burned rock and flake fragments recovered from the site suggest that tools were produced and repaired at the encampment.

No evidence was found that Native Americans occupied this particular encampment after the arrival of European settlers in the late 17th century. Local lore and evidence independent of the Eden Woolley Farmstead Site studies show that Lenape (as the region’s Native Americans came to be known) were present in other areas of what is today Ocean Township during the early years of European settlement. It is likely they, too, came here seasonally in small groups from larger communities inland.

An unexpected find

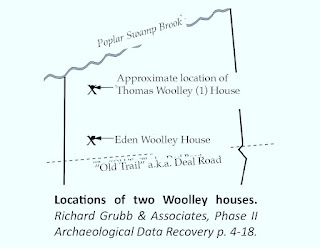

The investigation of the Native American encampment area yielded an unrelated, major discovery: the remains of another Woolley dwelling, predating the construction of the Eden Woolley House!

The archaeologists discovered a filled-in cellar measuring 20 ft. x 15 ft. and the remains of a brick staircase. The domestic, architectural, and biological items they found—together with historical records—helped them develop a theory of the structure’s lineage.

They believe the house was a one-room dwelling (at least initially), built by Thomas Woolley (I) between 1702 and 1705 on land purchased from Thomas Potter in 1697 by his father, John. Fragments of ceramic tableware none dating beyond the mid 18th century indicate the Woolleys were relatively well-off. The ceramics helped date the house, which experts believe was in not in use past the 1760s. Fragments of bones and shells point to a diet of clams, oysters, beef, and pork. It’s likely that the family raised cattle, pigs, and horses and grew corn, wheat, rye, and flax. Mention of a cider press in family records suggests the farm had orchards.

Thomas’s son, Thomas Woolley (II), inherited the property from his father in 1747. And here the story gets even more interesting.

At about this same time, Thomas (II) built the initial one-room structure of what we now refer to as the Eden Woolley House on the property to the south of the first dwelling. It appears the first dwelling was abandoned, its cellar filled, and some of its building materials reused to construct the new home.

Recognizing a rich, under-reported history

Among the items unearthed in the 2019-2020 archeological dig on the Eden Woolley Farmstead Site (the 32+ acres currently under development on the northeast corner of Deal Road and Route 35) was a Native American artifact estimated by the experts to be 8,000 years old.

Since the history that we know best is measured in centuries not millennia, this prehistoric relic challenges our imagination. What do we know about—do we begin to appreciate the history of the people who hunted in our woods 3,500 years before the first Egyptian pyramid was built?

Collapsing time

Our familiar history starts with the arrival here of European explorers and settlers—what historians call the Contact Period. It’s understandable. The Native Americans had no written language and left no written record. What we know of their history we piece together from the findings of archaeologists, oral traditions, and the accounts of the explorers, traders, and settlers who encountered them. The result is a collapsing of time. In the popular imagination, the image of the indigenous people documented in the 17th and 18th centuries defines our understanding of a people whose culture evolved over millennia.

Some meaningful distinctions

Although life did not change radically over the ages, there were distinctions and milestones worthy of note. We refer to the Native Americans of our region as the Lenape, yet this name was not used until the Contact Period. We call all manner of pointed projectiles arrowheads, yet the bow and arrow were not introduced until about 500 AD. We picture Lenape villages with longhouses, but for thousands of years, their population was sparse and their ancestors were largely migratory. For most of their history, the Native Americans of this region were exclusively hunters and gathers. Not until about 1300 AD did they cultivate crops—the iconic “three sisters” (corn, squash, and beans) we associate with them.

until the Contact Period. We call all manner of pointed projectiles arrowheads, yet the bow and arrow were not introduced until about 500 AD. We picture Lenape villages with longhouses, but for thousands of years, their population was sparse and their ancestors were largely migratory. For most of their history, the Native Americans of this region were exclusively hunters and gathers. Not until about 1300 AD did they cultivate crops—the iconic “three sisters” (corn, squash, and beans) we associate with them.

until the Contact Period. We call all manner of pointed projectiles arrowheads, yet the bow and arrow were not introduced until about 500 AD. We picture Lenape villages with longhouses, but for thousands of years, their population was sparse and their ancestors were largely migratory. For most of their history, the Native Americans of this region were exclusively hunters and gathers. Not until about 1300 AD did they cultivate crops—the iconic “three sisters” (corn, squash, and beans) we associate with them.

until the Contact Period. We call all manner of pointed projectiles arrowheads, yet the bow and arrow were not introduced until about 500 AD. We picture Lenape villages with longhouses, but for thousands of years, their population was sparse and their ancestors were largely migratory. For most of their history, the Native Americans of this region were exclusively hunters and gathers. Not until about 1300 AD did they cultivate crops—the iconic “three sisters” (corn, squash, and beans) we associate with them.A few basics

We do know that through their history the Lenape and their ancestors were a peaceful people. As their population grew and small villages emerged, they governed themselves as simple democracies. Some villages had leaders (called “chiefs” by the colonists). Extended families lived together in longhouses. Every family belonged to a clan. The clans were matrilinear, meaning they were made up of families related only through the mother’s side.